Yes, theyre back!

Author: Ivan Lätti

Photographer: Elsa Gouws

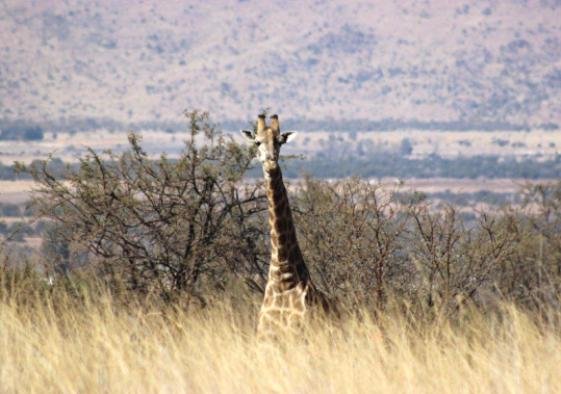

When the Tswana tribes lived peacefully in the Moot valley to the south of the Magaliesberg at the beginning of the 19th century, many game species including giraffe roamed around their settlements. The Tswana would never have thought that others would soon take over their world, shake it so much.

There were the red ants, the Pedi or Northern Sotho tribe that came in 1823, wearing red ochre war paint. The black ants, the Ndebele invaders under Mzilikazi, escaping the wrath of Shaka in what later became KwaZulu-Natal, came too soon after that in 1827. And only ten years later the riders on the animals without cloven hooves, the Voortrekkers or Boer horsemen took command with gun in hand. Probably never called the white ants.

Elephant, giraffe and much else soon disappeared from this territory for long or forever. A century later the farms were cut so small to accommodate all the farmer sons of mainly the Boers that farming for the conventional agricultural crops started to suffer. Legislation came to prevent further fragmentation of properties. Game farming became one option, at least to balance the mining risk.

In the 21st century smallholdings abound here, many of which serve only as a refuge for a Johannesburg or Pretoria city worker craving land; bush vegetation returning. Lumping properties together behind tall fences allows for the reintroduction in some places of game species not seen here for more than 150 years (Carruthers, 1990).