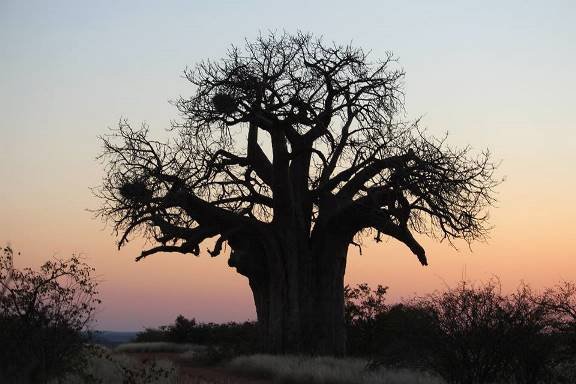

Adansonia digitata at sunset in winter

Author: Ivan Lätti

Photographer: Eric Aspeling

Any tree of such proportions receives full attention at first glance. As would any living thing of exceptional size. It is not size alone that supplies the magnetism of this baobab, although the shape is an unmatched ode to obesity.

Whatever is presented above that outsize trunk tends to the ludicrous. But let’s not poke fun at its girth. The tree’s magnificence is easy to admire and respect, while reserving comment on its “hat”.

These fibrous fleshy trunks have been transported by people to many parts of the world beyond Adansonia’s natural habitat, to greenhouses and gardens, public, botanical and private. Simply because people can. Access to resources, either public funds or significant private ventures have made baobabs and (Australian) baobs migrate.

Grown from seed is a viable alternative, but a later generation will experience such trees. So, Adansonia trees pop up far afield, beyond the three places where they normally grow, viz. tropical Africa, Madagascar and northwest Australia.

There are eight species of Adansonia. Only Adansonia digitata occurs in southern Africa. A. gregorii is an Australian commonly called a baob. Then there are six species on Madagascar, some magnificent specimens often seen in photos, better known than their country of origin itself.

The Australian baob is genetically so close to A. digitata that ocean crossing of the species is suspected, long after the Gondwanaland split occurred more than 100 million years ago. Floating seed pods sound farfetched, but unsolved riddles don’t easily ditch their outlandish solutions. Thus the possibility of aborigines carrying the seeds as immigrants between fifty thousand and sixty thousand years ago is also entertained (Leistner, (Ed.), 2000; Wikipedia; www.uq.edu.au).